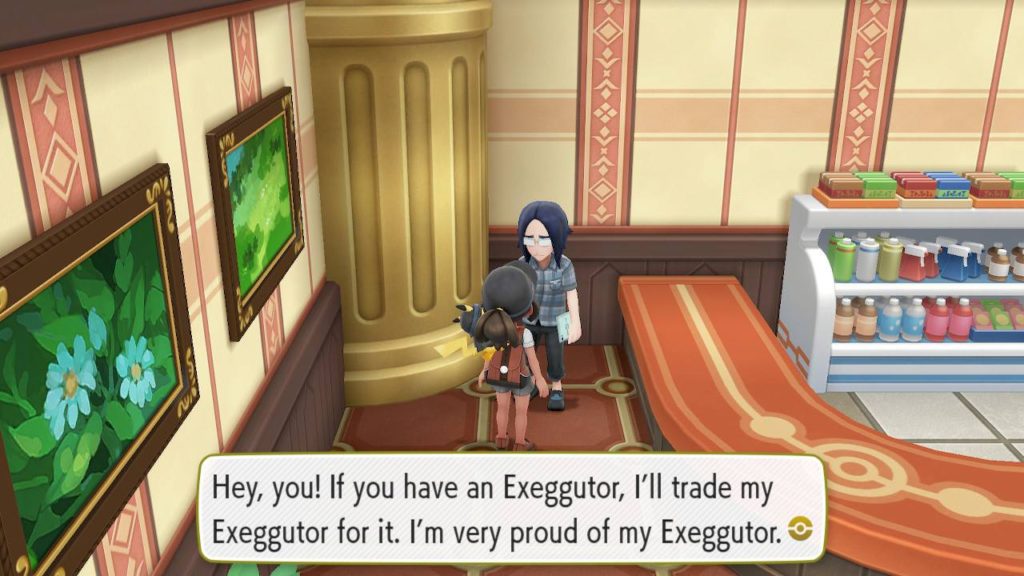

Suppose you are a pokémon trainer, and a fellow trainer approaches you with the following proposition:

In any real life scenario, this should be a hard pass. But the situation provides a teachable moment on two fronts to justify that claim.

Adverse Selection

Suppose someone tells you they want to engage in a trade. What does that willingness tell you about whether you should do it?

In many contexts, it tells you a lot. Imagine the Exeggutor was the strongest one could possibly imagine. Would the person want to exchange it for another Exeggutor? Absolutely not—no matter the strength of the other Exeggutor the person could receive in return, it would be worse than what he currently has. So a strongest possible Exeggutor would never be offered up in a trade.

Iterating this logic has an interesting implication. Consider the incentives of someone who has the second-strongest possible Exeggutor. Would that person want to exchange it? The only way this could be worth the time is if the other trainer has the strongest possible Exeggutor. But we just discovered that another trainer would not offer such an Exeggutor. So the person with the second-strongest should have no interest in trading either.

What about the third? Well, the only way this would be good is if a strongest or second-strongest Exeggutor were available. But they won’t be. So someone who owns the third-strongest should not engage in a trade either.

That logic unravels all the way down. Even a trainer with a very, very weak Exeggutor should have no interest in a trade. Although it is true that the average Exeggutor is much stronger than the one the trainer currently has, the average Exeggutor being offered for trade is not. In fact, trainers would only want to engage in a trade if the Exeggutor is the worst possible.

This result is well-known in game theory as a product of adverse selection—a situation where one party has private information about the value of a transaction. More specifically, it is an application of the market for lemons, which uses the same mechanism to explain why it is so difficult to buy a quality used car.

Cheap Talk

“But wait!” one might say. “The fellow trainer has assured me that he is very proud of his Exeggutor. It must be not so bad after all.”

Not quite. This is classic cheap talk. The message the other trainer is communicating could just as easily be conveyed by a trainer who actually thinks that his Exeggutor is terrible. Moreover, he does not have a common interest with you in communicating truthful information. Combining these pieces of information together, you should ignore the message altogether.

To make this more concrete, imagine that you were to take whatever the trainer said at his word. Then would a trainer with a truly terrible Exeggutor want to lie? If doing so would convince you to make the trade, then the answer is yes. As a result, you cannot differentiate between an honest assessment and a fib. In turn, the message should not change your beliefs about the Exeggutor’s quality at all.

Nintendo and Strategic Theory

All that said, this is Nintendo we are talking about. They are not interested in teaching you interdependent strategic thinking. The man actually has an exotic Exeggutor from a region you cannot access in the game. The only way to acquire such an Exeggutor is through a trade. You therefore most definitely should make the deal with him.

But this leads to a deeper question: why doesn’t the trainer just lead with that point in the first place? Rather than speaking to your common interest—he has an Exeggutor from his region and wants one from your region, you have an Exeggutor from your region and want one from his—he just speaks strategic nonsense.

Here’s hoping that George Akerlof appears in Pokemon: Sword and Shield offering the same trade. But this time, when you accept, you get a level 1 Exeggutor with all the minimum stats.