In my estimation, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild is the greatest video game of all time. There are a lot of reasons I think this is true. But, for now, I want to focus on the reason applicable to this website: game theory.

For the narrow set of readers familiar with both BotW and game theory, this might seem puzzling. Game theory is, by definition, the study of strategic interdependence. BotW is a one player game and would thus seem relegated to the field of decision theory.

On the contrary, a good portion of your play time is actually a two player game. It’s you and the game developer, and it’s a cooperative interaction.

Introducing the Game

BotW gives you the premise of the game-within-the-game right off the bat. As Link departs the Shrine of Resurrection, the camera guides you down a clear path. The first stop is a chat with the mysterious man at the campfire. Immediately afterward, Link finds a pointed ledge overlooking a pond.

Without telling you, the game is communicating a clear message. It is giving you a diving board shaped rock, equipped with its own water lily target. The game begs you to jump in. It then rewards Link with his first Korok seed.

Mr. Korok then tells you how the rest of this subquest will play out. Other Koroks are hidden, and you need to find them.

From here, the developers could have gone in two directions. One would have been a disaster. The other would make the game fun. They chose the latter.

Focal Points and Thomas Schelling

To get the fun, we must first take a step back and learn about focal points. In Strategy of Conflict, Thomas Schelling proposes the following problem. Suppose I instantly transport you and a friend to New York City. You have no way to communicate with each other but need to reunite. Where do you go to meet, and when do you do it?

This question has no “correct” answer. Anything you say—no matter how clever or ridiculous—could be right, as long as as your friend would say the same thing. Yet despite the infinite number of possibilities, Schelling found that people had a predisposition to choose Grand Central Station at noon.

Why? Schelling describes such a time and place as a “focal point.” They stand out for one reason or another, which makes them easier to coordinate on. Noon is the middle of the day, so it is a sensible time to meet someone else. Grand Central is a crossroads of New York, so it also seems appropriate.

The Developer’s Strategy

Nintendo could have placed the Koroks in the most obscure of places and make it as hard as humanly possible to find all of them. But they didn’t. Instead, they made a good faith effort to play a focal point coordination game with the player.

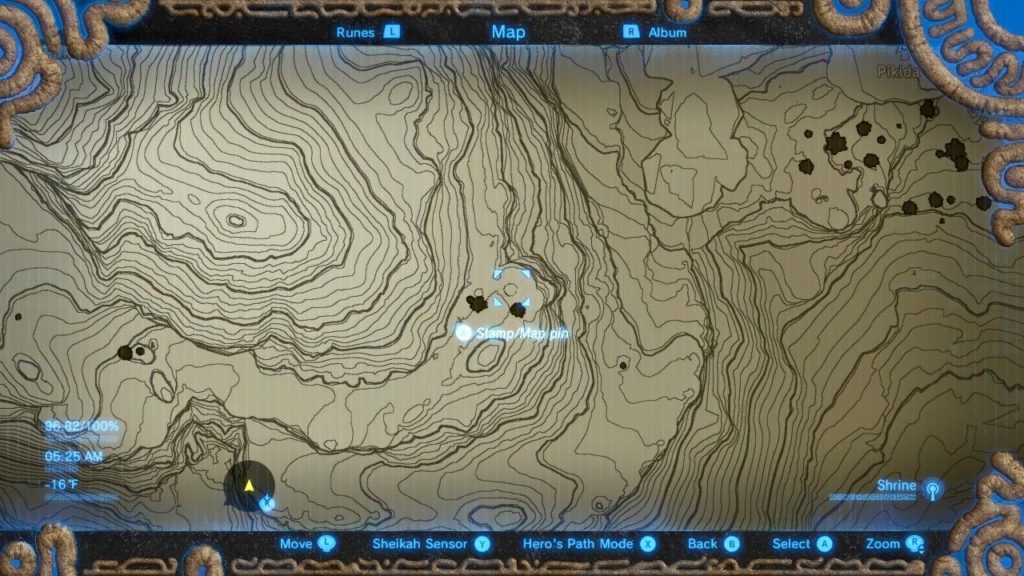

Open up your map and find another pool of water nearby? If you head there, a Korok is probably waiting for you. Is one tree much, much taller than the others? You should probably climb it. See a strange rock pattern in the distance? Time to investigate.

In fact, once you discover that category of Koroks, you look at your map in a whole new light:

Tons of these perfectly circular dots of rocks are all over the map. It makes you want to scour the map for more, and it excites you when you inadvertently discover one while using the map for something else.

Once you realize the game developers are trying to the Koroks easy to find, it completely changes your mindset. You start asking yourself “if I were a game developer who wanted to ‘hide’ Koroks in obvious places, where would I put them?”

Granted, not every Korok ends up feeling that way. The game has 900 of them, and the focal point is in the eye of the beholder. Many times, I was left dumbstruck and asking myself how anyone thought that someone could reasonably find that particular seed. Still, most of BotW rewards a type of strategic thinking that you rarely see in a one player game.