[The following is a lightly-edited and annotated transcript of the above video.]

This primary season is a rare time that results from game theory are receiving mainstream media attention. As such, it is worth a moment to talk about how the median voter theorem and turnout are affecting the battle between Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden.

Let’s start with the central argument Biden’s camp is making. It is basically an appeal to the median voter theorem. In practice, the median voter theorem says that, in a two-candidate election, the candidate with the ideological position closest to the median voter is most likely to win.

To diagram this, imagine we put every voter in the United States on a left-right spectrum. Here, to make things simple, let’s suppose there are only five.

We call the middlest-most person the “median voter”.

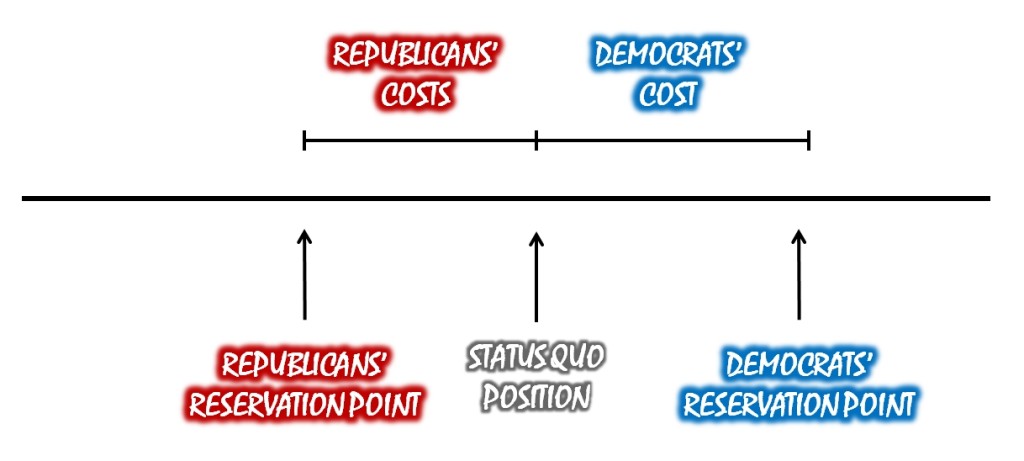

Now consider the ideological positions of Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Biden is a moderate democrat. He’s left-of-center, but not by too much. Trump, on the other hand, is far to the right.

If everyone votes for the candidate closest to their preferred position, whomever the median voter supports will win the election. This is because everyone on the left or everyone on the right will also vote in the same direction, and that is enough to guarantee more than half the vote.

Here, the median voter supports Biden. As such, Biden is likely to win.

In contrast, Sanders is a very progressive candidate. He has an ideological position far to the left. In fact, it is further to the left from the median voter than Trump is to the right of the median voter. Now the median voter supports Trump, so Trump is more likely to win the election. This is why moderate Democrats say that Biden is the more “electable” candidate.

Sanders supporters have an interesting counterargument. In their view, the median voter theorem isn’t “wrong”, just underspecified. Who the median voter is depends on who is turning out for the election. Their bet is that Sanders will inspire a bunch of young, liberal voters to come to the polls.

And with more liberal voters, the median voter shifts to the left. Now Sanders can win despite his ideology.

There are two counterarguments to the Sanders’ position. First, we haven’t seen young voter turnout rise substantially during the primary season.

Second, by the best we as political scientists can estimate, the turnout necessary to compensate for Sanders’ more extreme ideology would be unprecedented. That doesn’t mean it won’t happen—Sanders’ campaign has been historic for many reasons—just that it isn’t obvious that it will.

If you are interested in learning more about the median voter theorem, click the link for a lecture just on the subject. It’s also a topic I cover in Chapter 4 of Game Theory 101: The Complete Textbook.