With the death of Justice Antonin Scalia over the weekend, the scramble has begun to make sense of the nomination process. Senate Republicans are (predictably) arguing that the seat should remain unfilled until after the 2017 election, presumably so a Republican president could potentially select the nominee. Senate Democrats and President Obama (predictably) feel differently.

Overall, it seems that people doubt that Obama will resolve the problem. But most of the arguments for why this will happen fail to understand basic bargaining theory. That’s what this post is about. In sum, nominees exist that would make both parties better off than if they fail to fill the vacancy. Any legitimate argument for why the seat will remain unfilled until 2017 must address this inefficiency puzzle.

You can watch the video above for a more through explanation, but the basic argument is as follows. The Supreme Court has some sort of status quo ideological positioning. This factors who the current median justice is, the average median of lower court justices (which matters because lower courts break any 4-4 splits from the Supreme Court), and (most importantly) expected future medians. That is, one could think about the relative likelihoods of each presidential candidate winning an election and the type of nominee that president would select and project it into this “status quo” ideology.

Confirmation of a new justice under Obama would change that ideological position. In particular, Obama’s goal is to shift the court to the left. Republicans want to minimize the shift as much as possible.

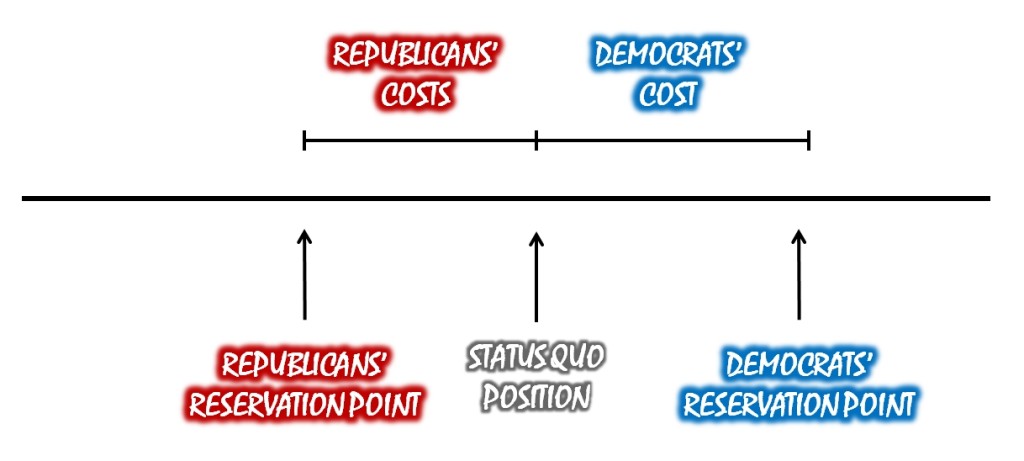

Nevertheless, failing to fill the position is costly and inefficient for the court. In other words, ideology aside, leaving the seat unfilled hurts everyone. These costs come from overworking the existing justices, wasting everyone’s time debating these issues incessantly, and generally making the federal government look bad. Due to these costs, each side is better off slightly altering the ideological position of the court in a disadvantageous way to avert the costs.

Visually, you can think of it like this:

(If that isn’t clear, I draw it step-by-step in the video.)

Thus, any nominee to the right of the Republicans’ reservation point and to the left of the Democrats’ reservation value is mutually preferable to leaving the seat unfilled.

This simple theoretical model helps make sense of the debate immediately following Scalia’s death. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell says “The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president.” But what he’s really saying is “Our costs of bargaining breakdown are low, so you’d better nominate someone who is really moderate, otherwise we aren’t going to confirm him.”

And when Senator Elizabeth Warren says…

Abandoning their Senate duties would also prove that all the Republican talk about loving the Constitution is just that – empty talk.

— Elizabeth Warren (@SenWarren) February 14, 2016

…what she really means is “Mitch, your costs are high, so you are actually going to confirm whomever we want.”

To be clear, the existence of mutually preferable justices does not guarantee that the parties will resolve their differences. But it does separate good explanations for bargaining breakdown from bad ones. And unfortunately, the media almost exclusively give us bad ones, essentially saying that they will not reach a compromise because compromise is not possible. Yet we know from the above that this intuition is misguided.

So what may cause the bargaining failure? One problem might be that Obama overestimates how costly the Republicans view bargaining breakdown. If Obama believed the Republicans thought it was really costly, he’d be tempted to nominate someone very liberal. But if the Republicans actually had low costs, such a nominee would be unacceptable, and we’d see a rejection. (This is an asymmetric information problem.)

A more subtle issue is that presidents have a better idea of a nominee’s true ideology than senators do. Maya Sen and I explored this issue in a recent paper. Basically, such uncertainty creates a commitment problem, where the Senate sometimes rejects apparently qualified nominees so as to discourage the president from nominating extremists. Unfortunately, this problem gets worse as the Senate and president become more ideologically opposed, and polarization is at an all-time high.

In any case, I think the nomination process highlights the omnipresence of bargaining theory. Knowing the very basics—even just a semester’s worth of topics—helps you identify arguments that do not make coherent sense. And you will be hearing a lot of such arguments in the coming months regarding Scalia’s replacement.